The life of my great-great-grandfather, Michael Haider, is shrouded in unanswered questions and a peculiar twist that leads to an unsettling demise. The lack of details about his birth, immigration, and his union with my great-great- grandmother, Catherine Lynch, paint an incomplete portrait. But, it is the circumstances surrounding his later years that make me the most curious, leaving me wondering: Why did he meet his end at the age of 46 within the confines of an Insane Asylum?

Michael journeyed to America at the age of 28, a determined immigrant from Hungary. Upon his arrival, he swiftly acquired a job utilizing his cooperage training. A cooper is trained to make or repair casks, barrels, and other similar containers from timber staves. Many coopers worked in breweries, making the large wooden vats in which beer was brewed. They also made the wooden kegs in which the beer was shipped to liquor retailers.

“It’s such specialized work, that in the past, the cooper was relatively very well paid. So out on the town, the cooper would be very well dressed and would mingle with the educated classes, however, because the work was so physical, a cooper could be given away by his rough hands.”1

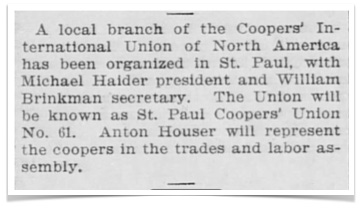

Michael was deeply committed to his trade, organizing and ascending to presidency of a local branch of the Coopers’ International Union of North America within a mere four or five years of his immigration, a testament to skills most likely honed in his homeland.

However, his narrative takes an unexpected turn in 1905, when, at the age of 43, Michael's vocation abruptly changed from a skilled cooper to the humble role of a street sweeper. The radical downgrade hints at the possibility of an unfortunate event that may have affected his ability to perform his duties as a cooper. Family lore tells a tale of tragedy – an incident at the Jacob Schmidt Brewery involving a keg that supposedly claimed Michael's life. In reality, what claimed his life is much more tragic.

However, perhaps there was an accident at the brewery in which Michael survived, albeit potentially incapacitated, steering him towards what would become an irreversible mental decline. The descent from a respected cooper to a street sweeper potentially became the catalyst for a profound melancholy that consumed Michael. But no matter how he got there, in 1906, he found himself committed to the Hospital for the Insane at St. Peter under the label of "Chronic Delusional Consecutive." Escorted by the Ramsey County Deputy Sheriff, the involuntary nature of his admission hinted at a struggle beyond the grasp of his family. Described as "demented, confused, suspicious and afraid," Michael had become an individual deemed unfit for home care. And now was identified as patient 2465.

St. Peter's Asylum for the Insane, a nearly 40-year-old institution by the time Michael was admitted, had long grappled with issues of overcrowding. Michael's arrival occurred in the aftermath of a desperate attempt to alleviate the overcrowding, where patients deemed “non-essential” were released. Like many asylums across the country at that time, St. Peter’s practiced primitive psychiatric care, with a treatment known as hydrotherapy, or colloquially, “the water cure.” In this treatment method, patients were held underwater until they lost consciousness, after which they were considered cured of their madness, assuming they survived. The more well-known, and equally barbaric treatments of electric shock and lobotomies did not make their appearance until the 1930s. For someone like Michael, who, according to his patient statistical record, was “sullen, irritable and resisted all treatment,” he likely underwent the “water cure”; was likely force fed at times and sedated by means of the use of a straight-jacket at other times. These types of treatments were so ineffective that more than 82% of patients remained institutionalized indefinitely.2

Little effort was made to separate dangerous patients from the melancholic. In fact, only one month prior to Michael's admission, a patient was violently murdered by another patient.3 This was not the first patient to be treated violently – either by other patients or by staff – and it wouldn’t be the last.

It’s not clear if Michael realized where he was or if he had any thoughts of missing his family. It’s also not clear if he ever received a visit from his wife or children during the two years, five months, and 15 days he was confined prior to his death in 1909. Interestingly, during the time he was away, he continued to be listed in city directories, living at home and working as a laborer for the railroad (a job that could have explained his absence). It was likely at this time that the family story of Michael having been killed on the job at the Jacob Schmidt Brewery began; perhaps an easier explanation for the children and neighbors given the era of mental health ignorance.

Although incomplete, the pieces of Michael’s life come together to reveal a narrative far from idealistic. On the contrary, what we know of his tale is a symphony of sorrow. His legacy invites reflection on the untold stories hidden within the branches of our family trees.

“Safeguarding an ancient tradition of cooperage,” Irish Independent. Last modified November 4, 2015, accessed February 7, 2024.

“What It Was Like to Be a Mental Patient In the 1900s” Video by Weird History. Last updated 16 Jun 2021, accessed February 8, 2024.

“Another Tragedy in “Lower Third”.” The Minneapolis Journal. Minneapolis, MN. 18 Sept 1906. Tuesday. Page 13. newspapers.com

Great story, and, after doing a bit of research on mental health and asylums during that same time frame, I'm not at all surprised the family continued to list him as living at home on documents, and fabricated tales to explain his absences. I'm curious, did St. Peter's have inmates enumerated in federal or state census records? I've come across a few institutions that did include this information.

We forget or fail to think about the problems of mental illness affecting our ancestors. Great story, really makes you think about early treatment and that this is not a new problem.