The Civil War Experiences of Thomas Stieren, both on and off the battlefield - Part 2

The war was just the beginning. The hardest fight came after.

Thomas Stieren, had been a soldier for only a short time, yet the war had already left its mark on him–not from enemy fire, but from the very animals that were meant to serve alongside him as a Cavalryman. First, a powerful kick to the chest during training had literally knocked the wind out of him and his youthful confidence. Later, on a scouting patrol, an untrained replacement horse lashed out, its hooves landing a brutal blow to his lower abdomen. Now, battered and weakened, he was being transported to Mound City Hospital, where the battle for his recovery was just beginning.

To read from the beginning:

~~~~~

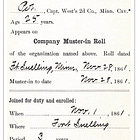

Mound City Hospital was located on the border of Kentucky and Illinois, a place where wounded soldiers like Thomas awaited an uncertain future. It was from here that Thomas began his journey home, a “Certificate of Disability for Discharge” in hand. The surgeon’s assessment was blunt: in his opinion, Thomas would “not again be fit for duty as a soldier during the term of his enlistment.”1

The words on that paper—and the crutches he still relied on—made it clear that he knew he’d never fully recover. Farming, the life that he had planned and dreamed of, was no longer a possibility. Not quite sure how he would manage to earn a living or be able to provide for a family he had once envisioned, Thomas may have felt lost for the first time in his life. Farming wasn’t just his future—it was his identity. And now, it was gone.

Hunched over in pain and swallowing his pride, Thomas applied for an invalid pension in Chicago on his way back to Minnesota. The label of “invalid” carried weight beyond its financial implications—it was a mark of dependence, a blow to a soldier’s dignity. And there is evidence that Thomas struggled with this. Though he submitted his application, he never followed through with the mandatory reexaminations required to maintain his claim. At best, he received $6/month for two years. More likely, and according to his own written testimony two decades later, he never received any payments.2

Instead, after a year of convalescence, he took a job in town as a saloonkeeper—a far cry from the open fields he had once imagined, but perhaps the only path left to him.

Over the next twenty years, Thomas married, had two children, and built a life around his work as a saloonkeeper. The job was not without physical demands—lifting barrels of beer or liquor, hauling crates of bottles, and keeping the place in order all required effort. He likely found ways to manage, resting on a stool behind the bar in between serving customers, unloading deliveries, and cleaning up at the end of the night. Over time, what may have started as a necessity became something more—he was good at his job, and he took pride in it. He understood his patrons, ran a respectable establishment, and found satisfaction in adapting his work to suit his limitations rather than be defined by them.

In fact, he was so successful at modifying his work environment that he began to dream bigger. If he could run a saloon, why not own one? If he could manage the daily operations, why not expand into something even grander? By hiring out the most physically demanding tasks, he could oversee a place of his own—a saloon, inn, and dance hall. At some point prior to 1881, he made that vision a reality, purchasing the “undivided half of the South 82 feet of lot 5 and 6 in Belle Plaine.” This section of land was undeveloped, but its prime location made it the perfect site for the business he had imagined.3

By the time Thomas was ready to make his saloon dream a reality, the landscape of Belle Plaine had changed and he was forced to sell his land. The economy staggered under the weight of repeated grasshopper infestations, and businesses that once thrived now struggled to stay afloat. For the first time since his discharge twenty years earlier, Thomas needed the pension he was due. What he didn’t need—and wasn’t expecting—was the bureaucratic gauntlet that stood between him and the financial support he had earned.

To begin his pension application, Thomas had to undergo a physical examination by an approved surgeon, the closest of which was 80 miles away by railroad in Mankato. If he had any doubt about the severity of his pain, the train ride erased it. Every jolt of the rail cars sent fresh waves of agony through his weary body. The stuffy, grit-filled air and relentless vibration turned the journey into a grueling test of endurance.

This trip held the promise of financial relief but also forced Thomas to confront his vulnerability. Swallowing his pride was the price of keeping his family cared for. But that bitter pill only grew harder to choke down when the surgeon’s report arrived: “no evidence of injury” to his chest or groin, only a right ventral hernia—enough to qualify him for a mere half-invalid pension of $8/month. It had already cost him $10 in legal fees to file the claim and another $6 for the roundtrip ticket.

An indignation that wouldn’t be the last.

In 1886, Thomas petitioned for an increased invalid pension. This time, he came armed with six affidavits from neighbors, a Justice of the Peace, and fellow soldiers who knew Thomas before the war. They attested to his declining health, recalling how they had often heard him “complain very much of his health in the store and hotel business” and affirming that he was “a good citizen” whose claim was “one of merit.”4

His pension remained unchanged.

Since 1862, veterans had been required to repeatedly prove their disabilities through medical examinations—a system designed to weed out fraud but which often denied justice to those most in need. And so, in 1889, Thomas returned for yet another evaluation, no doubt swallowing a bitter mix of shame and resentment. This time, he brought three new affidavits from well-respected neighbors. The words of two were especially blunt:

“They as neighbors to the claimant have been and now are well acquainted with him. That they knew him before he entered the “U.S.” service. That they knew him to be strong and healthy and that they knew him after he returned home after his discharge to be on crutches a long time. We know that he is troubled with heart disease and when excited or over-exercised he is subject to fits and is unable to perform manual labor since then his discharge up to date, unless it is light work, but to do farming he can not, because of heart trouble. He is only fit to keep office or Boundary House, when the wood is scavaged for him and the heavy work done for him as now the case with him.”5

Once again, the medical board found no evidence of his injuries—aside from the hernia. Once again, his pension remained unchanged.6

If his hands trembled as he left the doctor’s office, it wasn’t from age or illness but from the rage simmering beneath the surface. How many times must a man plead for what he had already earned?

There is evidence that the “approved” medical professionals evaluating the growing number of invalid pensioners were pressured to be scrupulous in their evaluations. And, it’s probably fair to surmise that visible injuries—such as missing limbs, shattered bones, or blinded eyes—garnered more sympathy than the internal ailments Thomas claimed.

Despite these obstacles, Thomas persisted. Every two years, as required, he reapplied—each time with new symptoms, new affidavits, and yet another medical evaluation. It wasn’t until 1900, at the age of 65, that his pension was finally increased to $10/month. But the relief was short lived. In 1902, with little explanation, his payment was reduced back to $8/month.

Thomas died in July of 1905, four months after his rate had been increased to $12/month—not for injuries, but for senility.

At the time of his death, he had six children—three by his first wife, who had died in 1872, and three by his second wife, whom he had married in 1876. She died in 1903. Two of Thomas’s six children were under the age of sixteen when he died, making them eligible for his pension.

They never received a cent.

~~~~~

For Thomas, the battle didn’t end on the battlefield. It followed him home, lingering in the relentless bureaucracy that questioned his pain, dismissed his truth, and reduced his suffering to fractions on a government form—half a man, half a pension, never whole. It’s only in reading between the lines of hundreds of pages in his pension file that the true weight of his struggle—his frustration, humiliation, and quiet desperation—comes into focus. He had survived the war, built a life, and raised a family, but in the end, the system he fought for never saw him as complete. And like so many others, he was left trying to balance a ledger that was never meant to add up.

Sources:

Bergemann, Kurt D., Brackett’s Battalion: Minnesota Cavalry in the Civil War and Dakota War (St. Paul, MN: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 2004).

Gibbons Bakus, Paige. “Everyday Life in a Civil War Hospital,” last modified December 5, 2024, accessed March 15, 2025. https://www.battlefields.org/learn/articles/everyday-life-civil-war-hospital#:~:text=Many%20of%20these%20hospitals%20were%20located%20in%20major%20cities%20such,D.C.%2C%20Philadelphia%2C%20or%20Knoxville.

Steinhoff, Ken. “Mound City, Illinois,” last modified December 13, 2014, accessed March 17, 2025. https://www.capecentralhigh.com/tag/mound-city-civil-war-hospital/

“The Civil War (1861-1865).” (2025, March 17). In Minnesota Historical Society. Historic Fort Snelling. https://www.mnhs.org/fortsnelling/learn/military-history/civil-war

“Minnesota and the Civil War.” Press Release 2012, December. (2025, March 17). In Minnesota Historical Society. https://www.mnhs.org/sites/default/files/media/kits/civil-war/civilwar_presskit_documents.pdf

Footnotes:

“Declaration for Original Invalid Pension,” digital image “Thomas Stieren” (2 August 1882), Civil War Records, Brian Rhinehart.

“Certificate of Disability for Discharge,” digital image “Thomas Stieren” (30 November 1862), Civil War Records, Brian Rhinehart.

"Scott, Minnesota, United States records," images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-C3W9-DCR5?view=fullText : Mar 31, 2025), image 172 of 651; . )

“General Affidavit for Any Purpose, (signed by William Henry),” digital image “Thomas Stieren” (10 April 1886), Civil War Records, Brian Rhinehart.

“General Affidavit for Any Purpose, (signed by D.H. Fearing and Robert Devine),” digital image “Thomas Stieren” (7 April 1889), Civil War Records, Brian Rhinehart.

“Surgean’s Certificate - Application for Increased Pension” digital image “Thomas Stieren” (2 January 1889), Civil War Records, Brian Rhinehart.

This is such an important piece of- for your family and for all of us.

As you said, there’s little doubt that Thomas’ experience with the war, his injury and then the pension process colored his life and thus the lives of his children. What that looks like and how it manifests will be interesting.

But, in the broader sense, Thomas’ experience is so relevant to the here and now, and echos what many veterans are experiencing today.

And cudos on your pension process research and analysis 🤩

My family wasn't here for the Civil War or any war prior so my experience with veterans and the issues they faced post-war started in WWI. It's sad that for every war fought, those who were in need of help had to continue to fight for it and were often denied. To continue to prove they needed help, swallow their pride, and deal with the shame, anger and grief time after time. Not to mention the strain on the family members and how all of the trauma from the war and life after trickled down through the generations. Thanks for sharing this piece of history. It helps bring awareness to the fact it isn't just recent veterans who suffered at the rules of others.