What do a German immigrant, a Polish telephone operator, and a coal-heated bungalow have in common?

They were all part of one small house's story.

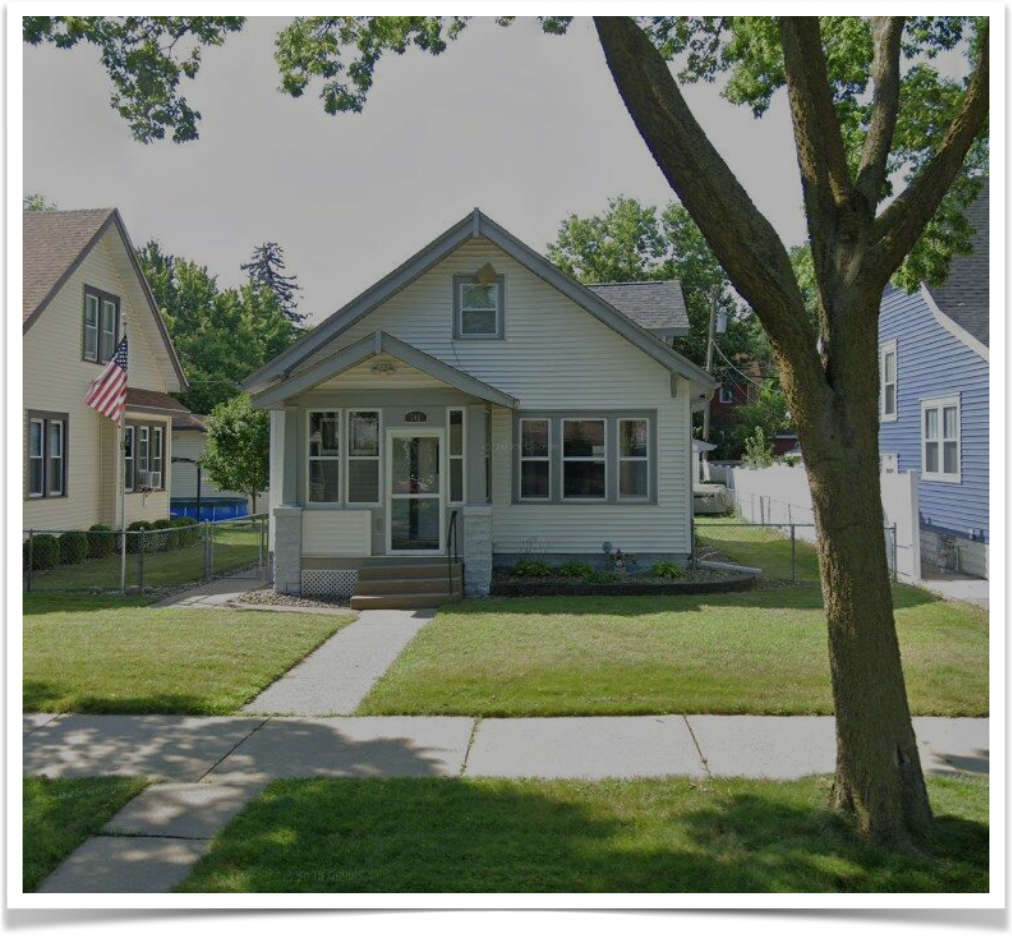

Below is the story of 746 Magnolia—a St. Paul home that held three very different families over the course of its first six decades. You’ll meet the people, peek into their lives, and maybe even be reminded of a house that lives on in your own memories.

A House Built for Two

The greater East Side of St. Paul has long been a working-class neighborhood. By the early 20th century, its grid of modest homes grew steadily in step with its industries: Hamm’s Brewery, Northern Pacific Railway, Seeger Refrigerator Company, and the newly relocated Minnesota Mining & Manufacturing—3M. In the Arlington Hills addition—carved out of open fields and scrubby oaks—worker homes were added block by block to keep laborers close to their livelihoods.

For years, Albin Johnson had walked past those fields. A quiet man in his early forties, Albin had lived as a boarder just a few blocks away on Magnolia Avenue. Each morning, he left for his job at the local sash and door company, where he’d worked for over 20 years as a machine operator. He and his wife Selma—both immigrants from Sweden—had long dreamed of owning a place of their own. In 1915, that dream became real when they contracted with local builders Stone & Gustafson to construct a simple but solid cement block home at 746 Magnolia Avenue East for $1,200.

Lot 9, Block 2. Just next to the only other home already standing.

Albin and Selma's house was smaller than their neighbor’s—just 947 square feet. But it suited them. They were childless. The house, with its 9-foot ceilings and simple lines, was built for two. Selma preferred the trim painted in blue. Swedish was still spoken in the kitchen. A coal chute fed the basement furnace, and in the evenings, warm air rose through the floor grates as they read or listened to the radio.

By the time World War I was winding down, the house on Magnolia Avenue had transformed from a simple 1917 bungalow into a thoroughly modern home for its time. A detached garage, added in 1928 at a considerable cost, announced the family's growing prosperity. Over the Depression years, they reroofed the house in 1930 and added fresh siding in 1937, keeping it sturdy against Minnesota's harsh winters. Minor plumbing and electrical upgrades hinted at slow but steady improvements inside. The house remained modest, but complete—efficient, tidy. For over thirty years, the Johnsons lived quietly on Magnolia Avenue, growing older as the neighborhood filled in around them.

In 1947 Selma passed away and Albin eventually decided it was time to move on—perhaps drawn to smaller upkeep. In their place came a new family, the Vanderbeeks, bringing with them a very different kind of household energy.

A House for Grownups

When Peter Vanderbeek and his wife, Olga, purchased the home in 1949, they brought not just their belongings but a cultural mosaic. Peter was 41; Olga, 38. They arrived with their teenage son, settling in just half a mile from where they had previously rented.

Peter had already worked for two decades as a foreman at National Wire & Cloth, a local manufacturer. He likely took the streetcar to the factory, his days structured by routine and precision.

Peter’s parents had immigrated from Holland in 1890. Though most of Peter’s older siblings were born in Minnesota, the family had moved to Germany in the early 1900s—where Peter himself was born. They returned to Minnesota when Peter was eight, and Dutch remained the dominant language in their household. He grew up straddling three cultures—Dutch, German, and Minnesotan.

Olga, meanwhile, had arrived from Poland as a young girl. In her childhood home, Polish was the language of lullabies and supper-table conversations. But by adulthood, she was fluent in English and working as a telephone operator—a role that required clarity, calm, and a knack for navigating other people’s needs. Peter and Olga likely married in the early 1930s, but official records remain elusive.

Together, Peter and Olga filled the home with the traditions of their youth. And Olga filled the backyard with beautiful flowers, setting off property lines in a delicate display of lushness. If you walked past on a Saturday afternoon, you may have caught the scent of kielbasa or heard polka music drifting from a radio. The house, though still modest in size, carried the sound of three languages—English, Dutch, and Polish—and eventually, it welcomed an aging member of the previous generation. Olga’s father came to live with them in his later years, spending his final days under the care of his daughter in the unfinished upstairs room. As with the Johnsons, the home was a place for grown-ups.

Though the Vanderbeeks made changes—most notably painting the trim a cheerful pink—the home remained much as it had been when the Johnsons left. Oil heat had not yet replaced coal. The layout was unchanged.

But change was coming again.

In 1971, a new family would buy the house, bringing with them a new language of sound: the giggles of toddlers, the rattle of toys on hardwood floors, and the chaotic joy of life with small children. The Petraseks weren’t just moving into a home—they were reimagining how it could be lived in.

A House for Growing Up

My grandmother, who lived two doors down, first learned that the older couple living in #746 were planning to retire and move to Arizona. She passed the tip along to my parents—newly returned to Minnesota after a brief attempt to settle in California. But a 6.5 magnitude earthquake had sent them back to more stable ground—both literally and figuratively.

So, in the fall of 1971, the house heard a sound it had never quite known before:

a baby’s cry.

Two babies, in fact—a six-month-old and a toddling two-and-a-half-year-old—whose giggles and shrieks soon echoed through the narrow hallways. Toys littered the floor. Sticky fingers found every surface. The once-pristine woodwork gained smudges, the kind that mark a home being truly lived in.

That fall, my parents—young, hopeful, and nearly outnumbered—became the third owners of 746 Magnolia. By the time they carried a third child through the front door two years later, the little house had transformed: no longer just a home for grown-ups, but a house for growing up.

They bought the house for $19,500, taking on their first mortgage—a daunting $79 per month. The trim was still pink when they moved in, a signature left behind by the Vanderbeeks, but it was soon repainted a cheerful green.

It had been nearly sixty years since the house had been built and the footprint of the house had remained unchanged—our family of five filled that 947-square-foot home. It was tight, but a fresh coat of paint and some carpet salvaged from a remodeled railroad car helped turn the small upper level into a bedroom for the two oldest children. The dormer nook became a playroom. My dad converted the house from coal to oil heating. Our house was filled with the sounds of a happy, albeit, money-strapped family.

The beautiful flower garden that Olga Vanderbeek had nurtured on the west property line was no longer in place, but along the east property line, twelve-foot lilac bushes bloomed each spring, fragrant and photogenic. The garage, built for a 1928-sized car, never once housed a vehicle while we lived there; it simply wasn’t big enough for anything newer. Winter mornings for my dad often began with snow scrapes and shoveling — never with a warm car.

I had lived in four houses before we moved here when I was just shy of 3 years, but my earliest memories begin inside this one. I remember walking three blocks to school in one direction, or a few blocks to the neighborhood library in the other direction. Family bike rides around nearby Lake Phalen. My sister breaking her leg on the neighbor’s swing set. (And then, once the cast was off, breaking her arm on the same swing set.) Playing “library” with our collection of Dr. Seuss books in the upstairs cedar closet. These are the details that have stayed with me.

And I remember my first friend. Julie Londino. She lived kitty-korner. We walked to school together. We went to Sunday school together. We played together almost every day. We started school together with matching lunch boxes. Born just four days apart, we celebrated our birthdays together every year.

When my family moved away to another state, I wasn’t allowed to give her a hug goodbye. I had chicken pox, and our parents didn’t want me to expose anyone else. I stood across the street, waving with one hand while clutching a tissue with the other. She stood on her stoop and waved back.

Saying goodbye to the house was easy, but it was the first time I had to say goodbye to someone I loved.

A House Remembered

The story of 746 Magnolia didn’t end when we drove away. The green-trimmed little house stood quietly as other families moved in and out, creating their own stories and celebrating their own traditions. I don’t know their names or the details of their days, but I like to think the house offered them what it gave us—a sturdy beginning, a place to grow into, and eventually, a place to outgrow.

Some of what it gave us followed us far beyond those walls. That very first friend I made at 746—the one I waved goodbye to from across the street with chicken pox and a broken heart—is still my friend today.

For its first sixty-five years, this house sheltered dreamers, retirees, and young families chasing something better. It held the scent of lilacs in spring and saw children run through the sprinkler in the summer. It stood steady through Minnesota blizzards.

Houses like this don’t usually make the history books. They aren’t grand or architecturally unique. But they matter. Because they are the backdrop for everything: scraped knees and Christmas mornings, whispered prayers and shouted arguments, the sounds of a family becoming itself.

Today, over one hundred years since it was built, the house still stands. The trim is still green. And while much has likely changed inside, I hope some small evidence remains—the creak of a certain step, the sway of the lilac bushes, and life-long friendships with the neighbors.

Not every house makes this kind of impression -- thank you for sharing this one!

This is so great ! You capture so many memory’s .