The Civil War Experiences of Thomas Stieren, On and Off the Battlefield - Part 1

The war was just the beginning. The hardest fight came after.

When I think of my 2x great-grandfather, Thomas Stieren, I picture an older man—weathered, composed, and wise. So, when I truly consider that he was only 25 years old when he volunteered for the Cavalry in the early years of the Civil War, I am taken aback. Yet, Thomas’s decision to enlist wasn’t made in a vacuum. The country was at a breaking point, and with no ancestral ties or generational loyalty to the Union, he stepped forward to fight for it anyway. Maybe he longed to prove himself. Maybe war felt like an adventure. Or maybe, after staking everything on a new homeland, he believed in fighting to keep it whole.

It’s hard to say for certain. But I do know that one year after declaring his intention to become a United States citizen, Thomas was among the first Minnesotans to enlist in the Cavalry. And for that, I am proud.

~~~~~

Confederate forces attacked Fort Sumter in April 1861, marking the official beginning of the War of the Rebellion. Though the Union had lost, hopes were high among the Northerners for a quick resolution. After all, the North had what the South lacked: resources for weapons of war. But then, in July, the Union was defeated at the Battle of Bull Run, and the determined resolve of the South became evident to men like Thomas. The South may not have had the industrial landscape to provide guns and ammunition like the North, but they did not let it stop them.

After the defeat, the Union government realized that the war would last longer than first expected and worked to raise more troops, including three cavalry companies in Minnesota. Thomas and five of his Belle Plaine neighbors volunteered for duty at Fort Snelling in Minneapolis, and were deployed to Benton Barracks in St. Louis, Missouri, for outfitting and training, arriving in late December.

Many people, these men likely included, thought of the cavalry units in a glamorous way—“seeing themselves charging the enemy while riding a horse and holding their sabers high.” In reality, Northerners were not trained horsemen. Owning a horse was impractical for country farmers who used oxen to pull the plows and other implements. Thomas was a farmer through and through. He had likely ridden upon a horse only a few times.1

Only the naivety and arrogance of the young can explain why Thomas volunteered for the cavalry with his lack of horsemanship. Most likely he had faith that he would be properly trained at Benton Barracks before being required to engage in duties. Like most recruits, though, he received only the barest instruction—how to mount, how to hold a saber, how to keep his rifle from falling from his hands at a gallop— before being thrust into service. The finer points of cavalry maneuvers would be learned in the field. Thomas struggled with the basics of riding and handling horses—a skill that normally took years to master. His inexperience led to a hard kick in the chest from his horse. The pain was real—any strenuous effort caused him to spit blood. He was scarcely able to endure a walk across the barracks, much less hard and heavy riding.2 But training was over. Orders had come: mount up, move out. With less than two weeks of training with a horse, and with a serious chest injury, Thomas was off to battle.

~~~~~

Three days and two hundred and forty-four cold and sleety miles later, the men arrived at Fort Donelson exhausted with half-lame horses in the early evening of 11 February. With burning thighs and stiffened bodies, they struggled to pitch tents in the frigid temperatures and frozen ground. The mercury was dropping fast, and blustery cold winds off the Cumberland River made it feel even colder. Soaked and shivering, Thomas collapsed onto the cold ground, too exhausted to care whether the horses were unsaddled.

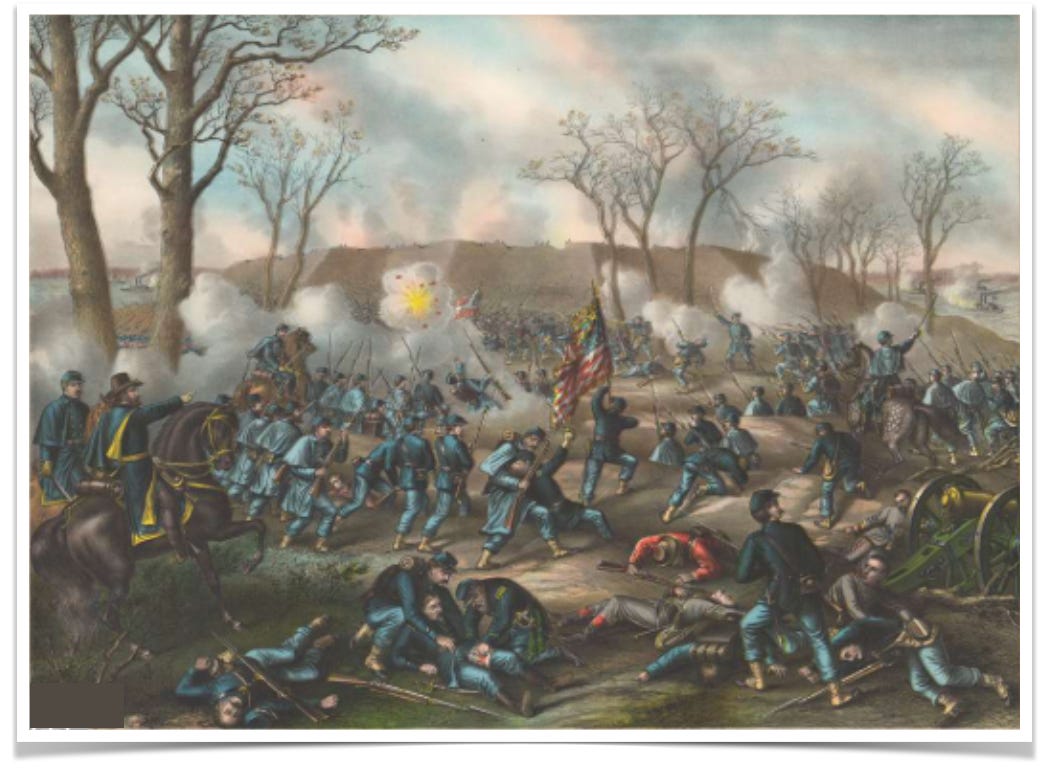

Nearly 41,000 troops took part in the battle for the fort over the next three days. At one point, victory for the Union was doubtful, but General Grant devised a strategy that would all but ensure success.3 While Grant’s army surged forward, Thomas and his fellow Minnesota Cavalrymen were sent thirty miles up the Tennessee River to destroy a railroad bridge. They arrived to find only a small force of rebels on guard that were easily dispersed, and the bridge was quickly burned without resistance. As young men, they may have outwardly conveyed the injustice of being kept from the glory of battle to accomplish what turned out to be a fairly easy task—but internally, perhaps, they felt relieved to be spared from the mayhem on the battlefield, especially Thomas whose breathing was still quite labored under any type of exertion. The cold, damp air wasn’t aiding his recovery.

The day after the bridge burning, the Confederates unconditionally surrendered. Brackett’s Battalion (named after Major Brackett who commanded the cavlary battalion) was the only Minnesota troop engaged in the battle of Fort Donelson, and while they did none of the severe fighting and lost no men, the work they performed contributed greatly to the Union’s first major win because the act of destroying the bridge opened the Tennessee and Cumberland Rivers to the Union navy.

“When the roll of the heroes at Fort Donelson is called, Brackett’s Battalion claims a place in the front rank.”4

Thomas had been enlisted for just over six weeks and was part of a group of men responsible for one of the Union’s first major victories. Despite the pain in his chest from the horse kick less than two weeks earlier, and potentially not realizing how pivotal his role was in the capture of Fort Donelson, his spirits were surely high. But that would be short-lived.

General Grant and his army famously moved south to Shiloh, while Thomas’s battalion continued scouting around the three forts in Tennessee and Kentucky—riding long distances, skirmishing with Confederate forces, and maintaining supply lines. The routine of the work didn’t make it more bearable. By summer, the air was punctuated with the odors of rotting horse carcasses. The climate was wet and unpredictable. The camps were rife with disease. The heat, sickness, and lack of proper food and supplies took a toll on morale. As bad as it was for the men, though, the horses of the cavalry had it worse.

The area around the forts had been heavily trampled and stripped of good grazing land after the battles. Corn and oats were in short supply, and grass and scrub were sparse. Between malnutrition and overwork, not to mention diseases like hoof rot from continuous exposure to mud and standing water—as well as saddle sores due to prolonged riding—the cavalry horses were suffering. By late summer, many were worn out, and acquiring new horses was no easy task. For Thomas, this would prove to be disastrous.

In September 1862, while on a scouting expedition near Fort Heiman, Thomas prepared to saddle a new horse. His usual mount had grown too weak for the demands of service and lay rotting in the nearby field, leaving him with an unfamiliar and likely unbroken animal. As he lifted the saddle into place, the horse shifted uneasily beneath his touch. Whether spooked by movement, discomfort, or sheer unpredictability, it lashed out without warning. A sharp, violent kick struck Thomas directly in the lower abdomen. The impact sent a shockwave of pain through his body, knocking him back and leaving him doubled over in the dust.

Men nearby rushed to check on him, but there was little immediate relief to be found. The injury left him in such severe pain that he likely temporarily lost consciousness. He was transferred to Mound City Hospital where, after nearly 60 days in the hospital, it became clear that Thomas’s injuries were not mere setbacks; they were permanent impairments that made his service untenable. What had begun as an ambitious enlistment ended with a forced return home.

“From Sept. 1862, until the time of his discharge, he was scarcely able to walk and entirely unable to ride.”5

Thomas was discharged for disability on November 30, 1862.

For Thomas, the war on the battlefield was over—but his greatest battle was just beginning. The scars he carried were more than physical, and the tests ahead would demand more than anything he’d encountered. What awaited him would shape the rest of his life in ways he could never have foreseen.

The second and final part of Thomas’ Civil War story is available:

Sources:

Bergemann, Kurt D., Brackett’s Battalion: Minnesota Cavalry in the Civil War and Dakota War (St. Paul, MN: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 2004).

Gibbons Bakus, Paige. “Everyday Life in a Civil War Hospital,” last modified December 5, 2024, accessed March 15, 2025. https://www.battlefields.org/learn/articles/everyday-life-civil-war-hospital#:~:text=Many%20of%20these%20hospitals%20were%20located%20in%20major%20cities%20such,D.C.%2C%20Philadelphia%2C%20or%20Knoxville.

Steinhoff, Ken. “Mound City, Illinois,” last modified December 13, 2014, accessed March 17, 2025. https://www.capecentralhigh.com/tag/mound-city-civil-war-hospital/

“The Civil War (1861-1865).” (2025, March 17). In Minnesota Historical Society. Historic Fort Snelling. https://www.mnhs.org/fortsnelling/learn/military-history/civil-war

“Minnesota and the Civil War.” Press Release 2012, December. (2025, March 17). In Minnesota Historical Society.https://www.mnhs.org/sites/default/files/media/kits/civil-war/civilwar_presskit_documents.pdf

Footnotes:

David Grosser, A People’s History of Belle Plaine (Shakopee, MN: Melchior Publishing), Page 89.

“Certificate of Disability for Discharge,” digital image “Thomas Stieren” (30 November 1862), Civil War Records, Brian Rhinehart.)

Fort Donelson. (2025, March 25). In Battlefields.org https://www.battlefields.org/learn/civil-war/battles/fort-donelson)

Sergeant Isaac Botsford, Narrative of Brackett’s Battalion of Cavalry (St. Paul, MN: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 2004), page 574.

“Officer’s Certificate to Disability of Soldier,” digital image “Thomas Stieren” (20 February 1863), Civil War Records, Brian Rhinehart.

I very much liked this style of story telling. The story in some ways is reminiscent of the account in the book "The Prairie Boys go to War" by Rhonda Kohl. It is a four year account of the 5th Illinois Cavalry told literally day by day. After reading it you feel like you've personally fought the Civil War. The difficulties you well illustrate were not unique unfortunately. Kohl's book relies in part on letters from the men which reveals their changing thoughts on the War, Commanding officers, slavery and their families back home. The 5th was more confined to the Missouri / Arkansas theatre.

This poor man. I can't imagine what he endured! I'm pretty sure I read about the bridge burning and Braddock's Battalion in "Killing Lincoln" by Bill O'Reilly.