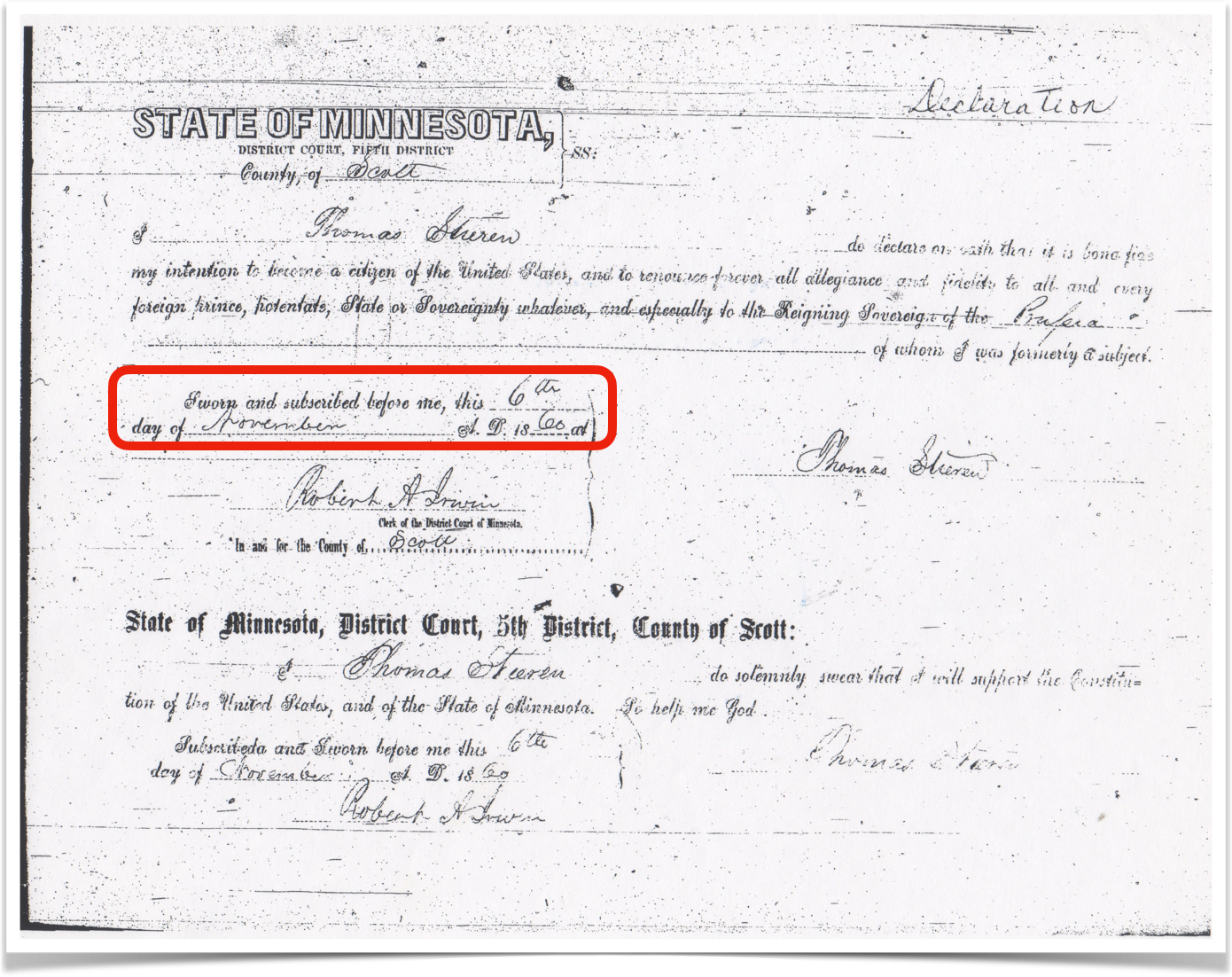

Thomas Stieren, my 2x great-grandfather, signed his “Declaration of Citizenship” paper (also known as “first papers”) on 6 November 1860. This is the same day that Abraham Lincoln was elected President of the United States. This story is a fictionalized account, inspired by real events, of what he may have been thinking at this moment in time, knowing that war would be imminent.

The cold mud sucked at the horse’s hooves with every step, a wet slurp breaking the weary silence of the road. Thomas shifted uncomfortably in the saddle, his legs stiff, his hands aching from gripping the reins too tightly. In his lifetime, he had spent hundreds of hours plowing fields behind the slow, steady pull of oxen, but this—this was something else entirely. Each time the animal slipped or lurched, Thomas's heart leapt to his throat, his body tensing instead of moving with the creature beneath him. The cold November rain had turned the road into a slick mess of deep ruts and hidden puddles, and after four grueling hours, his thighs burned, his coat was plastered with mud, and he wasn’t sure which of them—man or beast—was more miserable.

It was November 6, 1860 – voting day in America – time to elect the next President of the United States. Although Thomas was not yet eligible to vote, the significance of this particular election was not lost to him. A vote for Abraham Lincoln would surely mean war was imminent. But a vote for Breckinridge would mean a divided union. Thomas had reasoned that while neither option was ideal, a united union was the most logical – despite a war that would no doubt lead to bloodshed.

He had come to America two years prior, chasing the promises the state of Wisconsin had offered, with intentions of farming the newly admitted state’s rich soils, but by the time he had arrived, land prices had significantly increased for the few remaining decent plots.1

With seemingly few good options, he continued west, arriving in the newly formed town of Belle Plaine, Minnesota, along the Minnesota River. The population was small but hearty, with men – many of whom were from the Prussian empire like himself – willing to work hard to clear the land. His own Uncle Peter2 had a farm in the area and Thomas happily worked as a laborer while saving his hard-earned money. He had already managed to save $150 and was eager to put it towards the purchase of his own acreage.3 Perhaps just a few more months of laboring with Uncle Peter would be all it would take. He’d been eyeing up available plots around the area. He envisioned being able to clear his land, with the help of his new-found German neighbors, and then setting his mind on marriage and family-building. Yes, his future, he believed, was within his grasp.4

As Thomas neared the county seat, the road widened, its mud-thickened ruts gradually giving way to firmer ground packed down by the steady churn of wagon wheels and hooves. He reined in slightly, assessing the scene ahead. The quiet, lonely rhythm of his journey gave way to the energetic hum of a busy town. At the edge of town, he passed a wagon where a group of men had gathered, their breath fogging in the crisp air as they spoke in quick, animated bursts.

“He’ll bring war down upon us, mark my words,” one man declared, shaking his head.

A second, younger voice countered, “Better war than a country torn in two.”

Thomas caught only fragments as he rode past, offering a reserved smile, but the urgency in their voices sent a ripple of unease through him. His hands, stiff from the cold, ached as he gripped the reins. The sight of the blacksmith’s shop ahead drew him in like a beacon. The forge’s fire cast a flickering glow through the open door, the rhythmic clang of hammer on metal ringing through the air. He dismounted awkwardly, stretching out his stiff legs, and stepped inside.

A few men stood near the warmth of the forge, rubbing their hands together, their conversation hushed but intense. An older man with a thick white beard, his coat patched at the elbows, was recounting something in a gravelly voice.

“I was just a boy in ‘12, but I remember well enough. Thought it’d be over in a month. We all did.” He shook his head. “War’s got a way of stretching longer than any man expects.”5

Thomas flexed his fingers near the heat, listening. The weight of his own thoughts pressed heavier on him. He had believed, as many did, that a war—if it came—would be short-lived. After all, the North was far better equipped to win. He himself had observed the industrial landscape of New York, Pennsylvania and Chicago as he traveled westward from Ellis Island.6 But hearing the veteran’s words planted a seed of doubt.

Shaking off the thought, he grabbed an armful of hay, paid the smithie and stepped back into the street, leading his horse toward the courthouse. Voting day traditionally brought more folks to town than any other day, and today was no exception. A small crowd of men who had just cast their ballots were speaking in clipped tones, their expressions serious. Thomas tied his horse to the post near the water trough, cracked the thin layer of ice that had formed, and left the hay at the horse’s feet. He riffled through his saddlebag for a piece of yesterday’s midday meal. The ride had roused his appetite. He ate ravenously. He walked up the steps, cursing himself for feeling older than he was. “Verdammte Pferde,” (Damn horses) he muttered under his breath. He’d borrowed the horse from Uncle Peter, thinking it would be good to be able to learn to transport himself across distances, but now he was willing to give up self-transportation altogether if this was the cost.

Inside the courthouse, the air was warm and stale, reflecting the crowd of bodies and the scent of damp wool. After an hour or so, Thomas was at the front of the line. He removed his hat, nodding to the clerk behind the desk. The man barely glanced up, too busy dipping his pen into an inkwell and scratching names into his ledger. Thomas stepped forward. The clerk finally looked up, his expression neutral but expectant. “Name?”

Thomas understood the English language and could speak it in broken phrases. He offered his name and proudly said “I become citizen today.” The clerk smiled, nodded and began riffling through stacks of documents until he found what he was looking for. Thomas slowly spelled his surname “S-T-I-E-R-E-N.” The clerk motioned for him to place his mark. Thomas hesitated only a moment before pressing the quill to paper, the ink drying fast as the weight of his decision settled over him. “Lots of you Prussians here today,” the clerk said without making eye contact, “I hope you know what you’re getting yourself into. This election likely means war is coming.”

“I be here two years,” Thomas held up two stiff fingers, “I hear what happenin’ in this country. At least here,” he gestured around him, “my fate is not decided for me. I choose,” his finger pointed to his chest, “I choose,” he smiled.

The clerk looked up into Thomas’ blue eyes, passed him his completed “Declaration of Intent” papers and offered a respectful nod. Thomas took the paper, looked it over, folded it carefully and placed it into his leather folio, which he then tucked protectively under his coat.

As Thomas stepped back outside, the late afternoon sky had darkened, heavy clouds stretching across the horizon like an approaching storm. He turned toward the river, drawn by the distant whistle of a steamboat. Through the thinning fog, he spotted its dark silhouette pushing against the current, smoke curling from its stack as it made slow but steady progress upstream. He exhaled sharply, cursing himself for not taking the boat instead of enduring the grueling horseback ride. The journey would have been warmer, easier—he might have even dozed along the way. But then again, a man needed to know his horse, to trust it, especially if war truly was coming. That’s what Uncle Peter always said.

With a sigh, he mounted his horse clumsily, patting its damp neck. The animal flicked its ears, sensing his reluctance. As they started slowly down the road to find lodging for the night, his grip tightened on the reins. He had come here today expecting to take a step toward his future, toward land and a life of his own. But for the first time, he wondered if fate had other plans. He could feel the weight of the moment settle over him. This was the last quiet act before a future he could no longer control. A cold gust of wind came at him and he wondered if he would ever again know a day like this—a day before war, before decisions he could not take back. Still, as he straightened in the saddle, he knew this was the path he had chosen—and whatever lay ahead, he would meet it as a man building his own future.

THE FACTS:

Thomas’ early years have been difficult to trace, but from 1860 onward, there is a clear trail of documents, including his “first papers” which were signed on the day Lincoln was elected President. Almost exactly one year later, Thomas voluntarily enlisted in the Cavalry. Like many of those from his farming town, Thomas was not a confident horseman. At Benton Barracks in Missouri, where he was part of the Brackett’s Battalion, the Cavalry received scant training on riding and caring for horses. A few months later, the battalion was in Kentucky and Tennessee. According to his pension papers, he was injured by his horse on two separate occasions, rendering him “scarcely able to walk and entirely unable to ride.” He was discharged for disability in November 1862. He returned to Belle Plaine, unable to do much of anything in the way of manual labor, including farming; but he was hard-pressed to play invalid and be served upon. He became a saloon keeper, eventually owning and operating his own place of business.

New York, Passenger and Crew Lists (including Castle Garden and Ellis Island), 1820-1957,” database with images, Ancestry.com Thomas Strum, 1857.

Rev. Edward D. Neill, History of the Minnesota Valley, including the Explores and Pioneers of Minnesota Minneapolis, North Star Publishing Company, 1882. Page 331.

Thomas did live with Peter as documented in two census records. However, it is not clear if Peter was Thomas’ uncle. That said, it seems rather certain that Peter was a relation of some sort.

1860 United States Census, Belle Plaine, Scott County, Minnesota, digital image s.v. “Thomas Stearney,” Ancestry.com

There is a land record for a Thomas Stearns in Scott County dated 6 June 1857. Credence is allotted because the document was witnessed by Jeremiah Sullivan. Thomas later married Margaret Sullivan, Jeremiah’s daughter. However, the purchase date is one month prior to the supposed immigration date.

In 1812, the newly formed United States of America declared its first ever war on a foreign country: Great Britain. The conflict was primarily related to Britain impeding trade efforts between the U.S. and France. The war lasted almost three years. It is estimated that 15,000 Americans died. SOURCE: War of 1812 Facts. (2025, Mar 3). In American Battlefield Trust.

Most northerners supported the Civil War efforts of Lincoln because they believed that allowing states to secede would be unconstitutional. They also knew that the North was a “Titan of Industry” where natural resources were abundant for the manufacturing of guns, cannons and ammunition. Because of this, they believed the South was not equipped to win a war. SOURCE: The North and the South. (2025, Mar 3). In American Battlefield Trust.

I really really enjoyed this. Telling me upfront it was fiction and then having the facts at the end, actually invited me to think more deeply about this man and his life. This kind of family history really opens the past better than any history book could.

I can see this.

"The forge’s fire cast a flickering glow through the open door, the rhythmic clang of hammer on metal ringing through the air."