Lonesome: Grieving the Loss of a Child in the 19th Century

Unearthing the private pain expressed by Catherine Geenhan Corcoran in letters to her sister

In a certain light, it’s easy to believe that the death of a child in the 1800s and early 1900s, although sad, was common and therefore somewhat easier to overcome than it would be today. After all, there may have been other children to care for, not to mention the chores and routines of daily life that kept one’s mind occupied. Infant mortality rates were so high that a person likely experienced the loss of a sibling when they were young, potentially coming to believe that the loss of a child was to be expected.

But, in a truer light, the loss of a child was devastating, no matter the circumstances. The letters of my 2x great-grand-aunt, Catherine (Geehan) Corcoran (who went by Katie) offer a rare glimpse into the heartbreak that consumed her, revealing how deeply the loss of two of her children affected her spirit. In these personal writings, the rawness of her emotions is exposed—her attempts to process the unimaginable loss are framed in the simplest yet most poignant of terms.

February 20, 1892

My dear Sister

. . . We lost our baby. We feel very lonesome for him. He was a very good baby. His name was Timothy. I am not very strong myself yet but I am getting better now . . . I did not get strong after the baby was born for a long time. When the baby was sick [a friend] came and took care of him until he died. The dear little baby. He was so quiet. He was not much trouble. Pat liked him very much and wanted Papa to bring him back . . . I feel so lonely for him.1

Katie’s use of the word “lonesome” in this context is especially poignant. It evokes not just sorrow but a deep sense of isolation and emptiness. The repetition of “lonesome” and the emphasis on how much her 2-year-old son, Pat, missed their baby shows that the loss pervaded every aspect of daily life. This wasn’t something they simply “got over,” as is often assumed about child loss in the past. It is worth noting that even though Katie doesn’t mention her husband’s grief specifically, she has included him by saying “We feel so lonesome.”

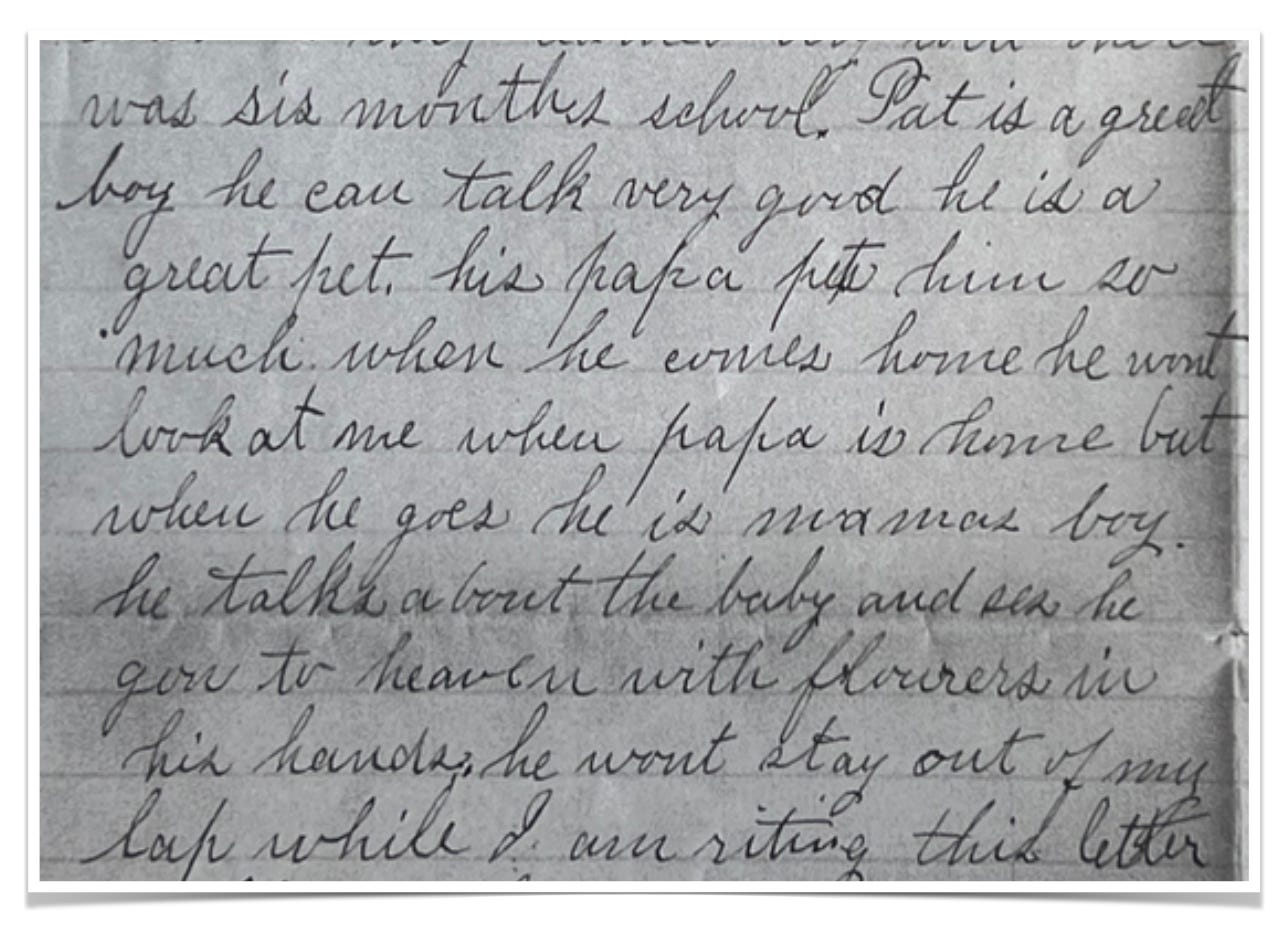

In a letter written a few months later, Katie explains how Pat often speaks of his brother and says that he has “gone to Heaven with flowers in his hands.” This suggests that the family openly grieved and allowed the young children to express their grief. Despite what has commonly been perceived, the death was not something brushed under a rug and the surviving children were not dissuaded from extra hugs and coddling.

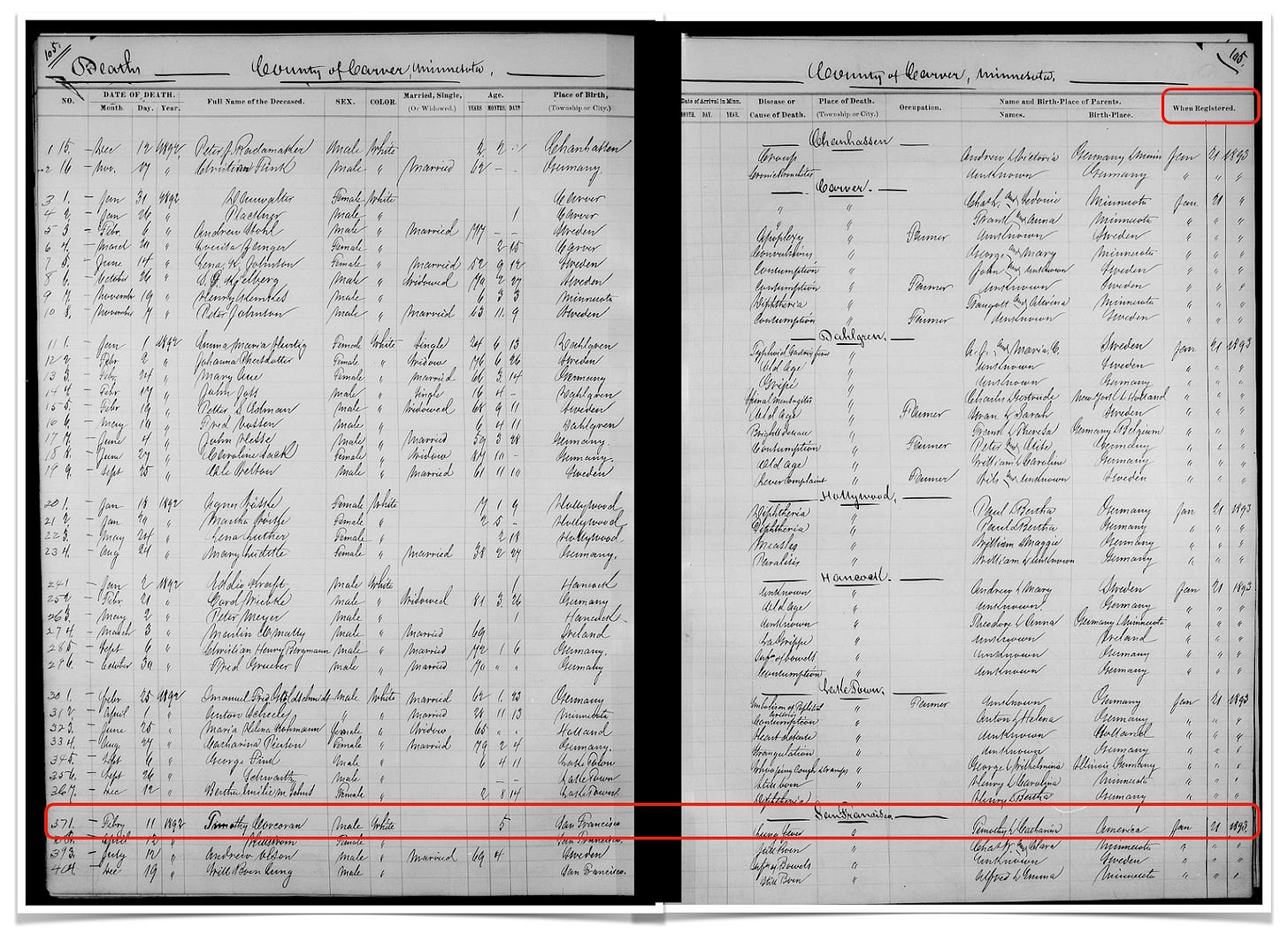

According to county records, Timothy’s death was not registered until 11 months later. The registration delay speaks volumes about the extent of Katie and her husband’s anguish. It’s more than just an administrative task they put off; it reflects their emotional struggle to confront the finality of his death. This is a subtle yet profound example of how grief can manifest in the mundane details of life.

After the family’s grief over Timothy, they faced another heart-wrenching blow: the lingering illness and eventual death of her eight-year-old daughter, Mary Alice.

August 23, 1893

My Dear Sister,

It is with a sad heart that I am writing to you to tell you of my dear little Alice’s death. She died the 10th of August. She was sick nearly nine weeks, and inflammation of the stomach was what she died with. The priest gave her First Communion and anointed her the 8th of August. He told me she would not live but a few days. She used to get up every day and sit and walk a little. The day she died she got up and walked out after her papa to the door. She got so old-fashioned in her talk that she used to make me cry listening to her. For I always thought she would not live. She used to say when she would get [really sick] “Oh mamma maybe I am going to die tonight.” But she did not like to leave her mamma, she said, because I would be too lonesome for her. She got so thin before she died. She was nothing but skin and bones.2

The line “she got so old-fashioned” suggests that Katie not only saw her child’s physical decline but also observed a profound shift in little Alice’s emotional and mental state. It is heartbreaking because it shows that Katie watched her daughter mature prematurely, perhaps as a coping mechanism for the sickness, making her seem older and wiser than her years, which was in contrast to the short life she lived.

A few months later in November, Katie wrote about her children going off to school and how she was lonesome for Alice, who should have been going along with them.

. . . [the children] are going to school. It is so lonesome not to see Alice with them. I feel very lonesome all the time. She is better off I hope. We must be satisfied with the will of God.3

Mary Alice’s death carries its own unique kind of devastation. Losing a baby like Timothy is its own profound grief, but to lose a child after eight years of shared life, experiences, and memories feels like tearing away a piece of one’s soul. The phrase “I feel very lonesome all the time” is particularly poignant. With the older children off to school and her husband away during the week for work, Katie was quite literally alone all day. She must have felt her daughter’s absence at every turn.

Reading letters like Katie’s feels deeply personal, almost like stepping into her most private moments of vulnerability. But these letters also remind us that the depth of sorrow is universal—no matter the era. Through her words—and even her silences—Katie’s heartbreak speaks to a shared human experience of love and loss that echoes across the generations.

How have your ancestors expressed their grief over the loss of a child?

Catherine (Geehan) Corcoran. Letter to sister Bridget Geehan dated 20 February 1892. Copy of letter in possession of author. Transcribed by author with edits to text including spelling and punctation to aide in readability. ChatGPT was an invaluable partner in gleaning insights from the letters.

Catherine (Geehan) Corcoran. Letter to sister Bridget Geehan dated 23 August 1893. Copy of letter in possession of author. Transcribed by author with edits to text including spelling and punctation to aide in readability. ChatGPT was an invaluable partner in gleaning insights from the letters.

Catherine (Geehan) Corcoran. Letter to sister Bridget Geehan dated 11 November 1893. Copy of letter in possession of author. Transcribed by author with edits to text including spelling and punctation to aide in readability. ChatGPT was an invaluable partner in gleaning insights from the letters.

Oh, Kirsi, that's just heartbreaking. I haven't so far uncovered letters or diaries, but gosh what a treasure. They share what must be a universal anguish. 😢

I don't have any written record of the grief of my ancestors, but I know the trauma is real. My grandmother was born in 1901. She came from a large Irish family and lost several siblings at a young age. She never talked about her family. It was a sealed box. She never revealed that she had a a sister, who died in 1919, or a brother, who died in 1923. Or any of the other family members who had died before them.